Our tea recipe is weird

But it comes out perfect every time

Our tea recipe is weird

But it comes out perfect every time

Let me start by saying

You might find yourself upset about the things I say about tea here, and I want you to know, that's okay. You have the right to feel what you feel, and to make it easier I'm going to get it out of the way and say up front: yes, Yorkshire Tea is far inferior to our Thompson's. You're wrong, and I know that's upsetting to come to terms with.

I'm here if you need a good cuppa, since you're lackin one.

Anyway, let's get to the point.

Well, maybe not right away, but eventually, I promise. So let's get to the stuff that eventually should get to the point (will it? (yes (I mean I hope at least))).

My wife and I both come from cultures where tea is pretty central to daily life. The teas our families make are not too dissimilar despite being 5,523 km apart, but the methods they use are rather different.

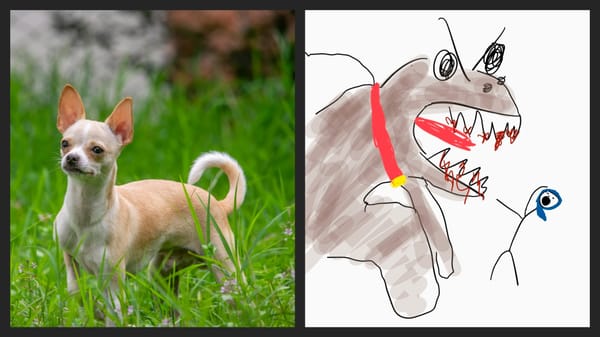

Every tea-making culture knows well their neuroses about the method of producing a drinkable cuppa.

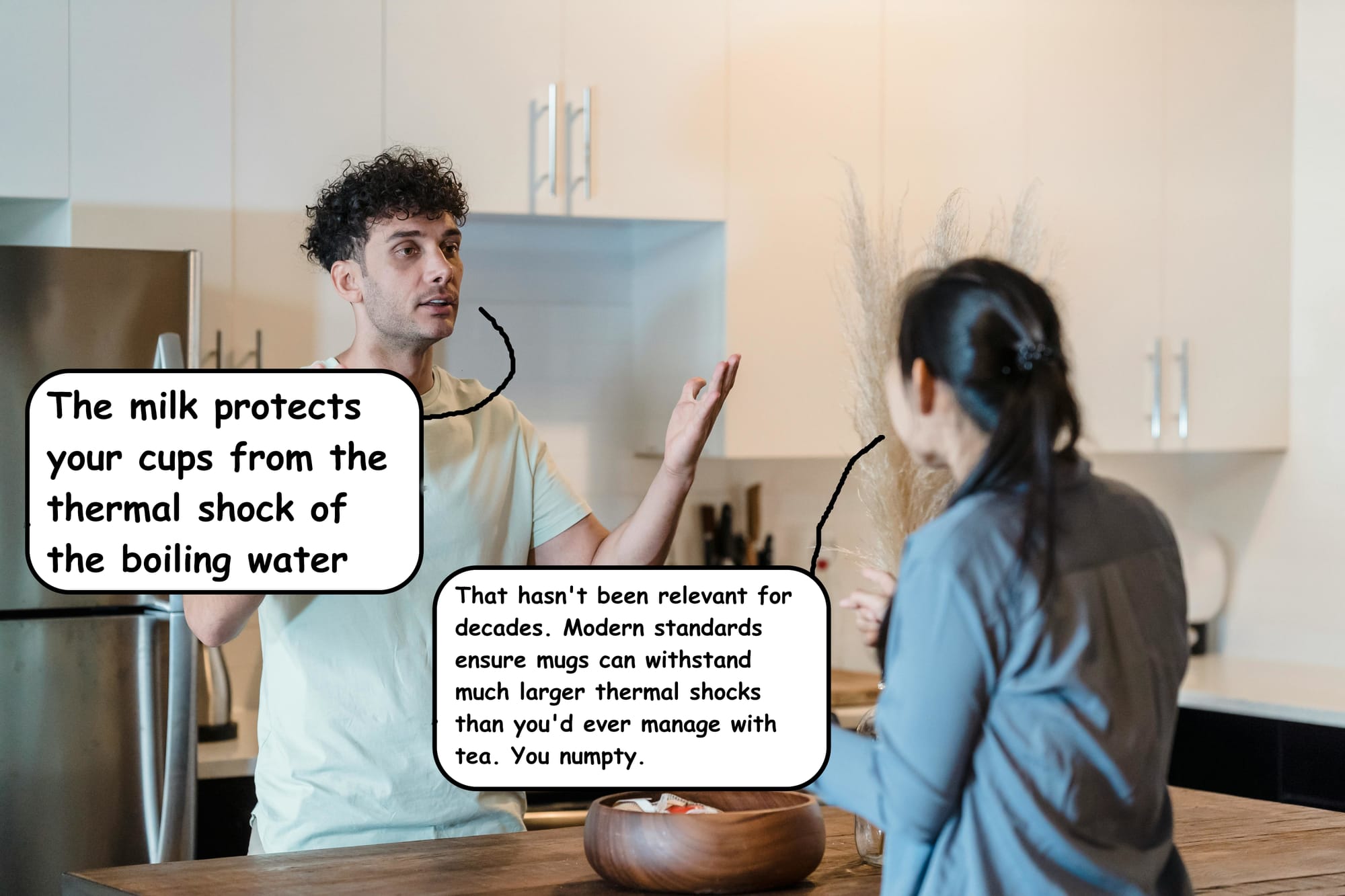

In Northern Ireland, folks' methods are pretty congruent I think, modulo some back and forth on milk first or second. Boil the kettle, chuck a couple of Punjana teabags1 in the teapot, pour the water in when the kettle clicks off, let it steep.

Don't rush the brewing time. Too weak and people will let you know you've done them wrong. The mood will turn dark, oppressive will be the looks of disdain, and your reputation will be forever sullied as "yer man who makes weak tea".

You'll have known by now how everybody takes their tea, so you'll arrange the milk (& sugar if they're one of those types) to each of their tastes, and carry it all in. Of course, you follow that with a plate of biscuits as well.

Well that all seemed pretty normal

The title of this post might have you wondering where I'm going with this. And well, I've just walked you through the recipe we follow at my parents' house.

Here in our flat in Denmark, we don't own a kettle (gasp), mostly to save counter space, and the fact we've got an induction hob that boils water virtually instantly.

For those dreading a sub-boiling brew, or a microwaved mug of water, I can allay your concerns.

We're not American.

The process will sound somewhat more familiar to those of our family living 5,523km away from my parents' house, but the final result in the mug is virtually indistinguishable from the tea I described above.

Add the requisite amount of water to a saucepan, and bring it to a fast simmer. Add an appropriate amount of loose-leaf tea to the water, and let it continue at a simmer for a bit. Meanwhile, preheat the correct volume of milk so it isn't fridge-cold and add it to your teapot.

When the water has been rightly reddened by the tea, bring it briefly to a hard boil, let it settle down again, and bring it once again briefly to a hard boil. Pour the tea through a strainer into the teapot, swirl to combine with the milk, and serve.

I'll have to ask you to believe me when I say, this tea tastes basically the same as the tea from the other method.

Two paths reach the same destination

At this point, we've a pretty good understanding of what is most important when making this kind of tea.

You've gotta hit the tea with 100°C water, extract enough to get to the right strength, and add to it the amount of milk that matches your taste. Both methods achieve these goals, both defined through trial and error, both eventually settled upon as routine once the balance was found.

So why are we so prescriptive?

I think there's a certain comfort in having procedures; guardrails to make sure things stay within specification. There's safety in a checklist that's been tested, that you know will give you the result you need without waste, mental strain, or injury. You memorialise those who came before, honouring their efforts to light the paths you now walk.

I think though, that we owe it to them and ourselves to elevate our experiences, by working to understand why we use these techniques, why it all works, and through that, sometimes we can stumble across new paths we can light ourselves for those who come after.

One Flatbread to Rule Them All

Every one of us who's lived outside of Northern Ireland knows, you must leave a spot in your suitcase to bring potato bread back with you when you go. It's virtually non-existent once you leave the UK, and we all get the craving when it's been a few too many months without it.

Truly, there's nothing quite like it, and everybody I've given it to finds themselves enraptured by the luxury of texture and taste hidden within this deceptively modest flatbread.

Now the thing is, to make potato bread yourself, you really have to know your potatoes. That is to say; the recipe isn't, and cannot be, authoritative in terms of measurements - any recipe that starts by telling you how many spuds and how much flour you'll need, is gonna lead you astray. Inspired by the whispers of the devil they are, and salvation can only be found through the proper handling of your potatoes.

Now I've gone through a lot of experimentation when it comes to potato bread, and I've ended up making two adaptations that are not traditional, but that help to produce better potato bread than even the ones you buy back home.

Roti-inspired Potato Bread

Get this

- Leftover mashed potatoes

plain flour→ chakki atta

This is my first adaptation. Rotis only have 2 ingredients: water, and chakki atta. It's a type of flour that's high in gluten, using the whole grain unlike refined white flour. If you try to make roti with your plain flour, it's not gonna work.

I've tried making potato bread with plain flour, whole wheat flour, and chakki atta, and the latter has the best texture while retaining the flavour you know.

Do this

- You want to start by mixing about equal volume of your flour to your mash, adding more flour gradually and mixing well with your hands each time.

- Your target is a dough that sticks to your fingers when gentle, but not when you slap it.

- Flour a surface well, and form the dough into spheres the size of overfed golf balls.

- Now to cook them. You can do this in a non-stick pan, or a griddle, but my second adaptation comes into play here. I use a roti maker.

- Whatever you're using, get it frighteningly hot. If it's too cold, it's gonna stick and fall apart. Put a ball in, and flatten it to around 5mm thick. Flip it once when it's browned and freckled on the first side, and remove when the second side matches.

Best served after frying or toasting it, with breakfast food.

If you wanna do them a bit bigger and cut them into farls, you can feel free, but they won't taste different.

But it's not authentic

Look, I believe traditional recipes exist for a reason, and sometimes you just can't beat them.

Every time I start making a shepherd's pie the same way we always make it, I find myself wondering if I should make some adaptations or try something new with it. Then when I'm eating it I pause. This was perfect, there's nothing that needs messed with here2.

There is a case to be made for preservation of culture through food, and it's important that by learning our history and exploring new techniques, we balance retaining our culture, and developing it.

If somebody came along saying their shepherd's pie is filled with a beef ragu and has a sweet potato topping, I'd raise an eyebrow at the suggestion a shepherd's pie would contain anything but sheep, and be topped with anything but regular spuds.

There's a strong cultural tie to the ingredients we use, a history of people and survival under colonial oppression.

That's for us though. If you think that beef and sweet potato shepherd's pie sounds neat, nobody can stop you from making it in your own home, and nobody can stop you from finding it delicious3.

I guess what I'm trying to get at is, our traditions are to be celebrated, but not to be rigid. Being born out of circumstance, they've always been malleable up until now, and they'd not be what they are if they'd been forced to stagnate through strict adherence.

Where we came from is enshrined in our grannies' recipes - shepherd's pie, stew, potato bread, soda bread, the lot. We have to keep half a mind on their memory, and the other on a future we'd be proud to pass on.

- At the very least it ought to be one of the Thompson's blends of black tea. We're not in Yorkshire folks, forget about that Twinings slop, and if any one of ye brings up Pickwick I'll give you a slap round your ears

- Not giving this one away sorry, I've gotta save some secrets for when you come over for dinner now don't I?

- nobody can stop me from calling you a monster